Imagine language as a painting. Grammar and syntax provides the frame and the canvas. The pigments that play across this surface? Vocabulary. But what is responsible for the blending, shading and distinctly painterly touch with which these colors are applied? Intonation is perhaps the most subtle and most difficult to master aspect of any new language.

What is intonation?

People often claim "tones" are specific to Chinese languages (and a few others), however this is not entirely true. While the vast majority of Western languages are not tonal, speakers of English and the Romance languages (Spanish, French, Portuguese, etc.) do frequently use variations in pitch to add connotative meaning to words and sentences. For example, a rising tone of humorous incredulity at the end of an English sentence can indicate that it is a question.

However, rising and falling pitches in Mandarin produce actual denotative differences. The way in which individual syllables are pronounced changes the essential meaning of word. For example, most English speakers would recognize the phoneme “da” as an irreducible unit of meaning. The only consequential difference between “da” and another syllable would be either a change in the leading consonant sound—e.g., ma—or the terminal vowel sound—e.g., do. However, in Mandarin, “da” can be pronounced at least four different ways, thus “translated” into four very different words:

dā (搭), “to hang over; to hover”

dá (答), “to answer or reply”

dǎ (打), “to beat; to fight”

dà (大), “big; huge; great”

Mandarin tonalities

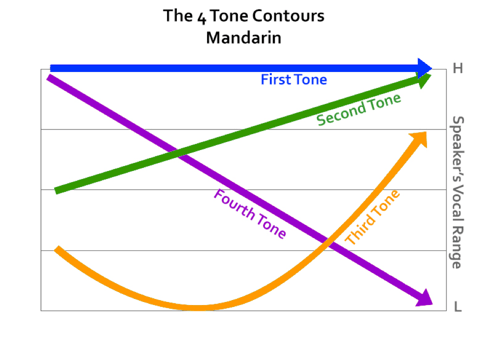

Mandarin pronunciation employs four basic tones. These tonal variations are indicated in Pinyin (a transliteration of spoken Chinese that uses the Roman alphabet) by use of what are called diacritical marks.

- First Tone: begins in and stays at the the upper register of the individual speaker’s vocal range, with no deviation, (ā)

- Second Tone: rising from a middle register to the speaker’s highest register (á)

- Third Tone: sweeping down from a middle-lower register to the lowest register, then rising towards the highest register (ǎ)

- Fourth Tone: descending quickly from the highest to the lowest register (à)

Mandarin technically includes a fifth tone. This “neutral tone” has no contour; it is “flat.” Like vowel sounds in English, the fifth tone is largely contextual. This means that the pitch of this fifth tone depends almost exclusively upon the pitches that either follow or precede it. Linguistics refer to the process by which individual tones shift in both sound and accent (or emphasis) as they are strung together in longer utterances, as tone sandhi. “Sandhi” comes from the Sanskrit, one of India’s 22 languages. In that tonal language, “sandhi” means “joining.”

We can also visualize the four chief tones of Mandarin using a graphical system that, not coincidentally, resembles musical notation.

Indeed, this emphasis on pitch perhaps explains why some English speakers detect a “sing-song” quality in spoken Mandarin. Linguistics describe the movement between pitches described above as contour. No matter how extensive your collection of dictionaries may be, then, the way in which you shape your sounds is of considerable importance if you wish to be understood by other Mandarin speakers.

What are tone pairs?

Every language seems to possess a unique sound that is challenging for non-native speakers to fit in their mouths. Italian has the “gli,” and Swedish its “sj-sound.” Even English has its infamous “silent letters”: the “k” in “knife,” the “h” in “hour,” the “i” in “business.” However, as with Mandarin’s four tones, just getting the pronunciation of these isolated sounds right is not enough to achieve fluency. The key is to understand how these distinctive sounds combine to form larger units of articulation. For example, in conversation, the third tone described above starts low and stays low, just as the first tone starts high and stays high. However, the third tone can be subject to other subtle changes, depending on what tone pair it's in!

THE TONE EXCEPTIONS

When two third-tone Chinese words appear in succession, the first third tone is instead pronounced with the second tone. A classic example of this is the Chinese word for hello, “你好 (nǐ hǎo).”You’ll notice that the pinyin indicates two third tones, but it’s actually read as “ní hǎo.”This is an easy exception to remember, since saying two third tones in succession is actually rather difficult.

Another tone exception is the word for “no / not”, which is “不(bù).” On it’s own, “不” is read with the fourth tone, “bù.”However, when you read it in a phrase such as the word “no,”it takes on the second tone:“不是(bú shì.)

Tones Dictate Meaning

Many of the most frequently used words in contemporary Mandarin are disyllabic. They consist of two syllables and are often transcribed using two characters. The Mandarin word for “identical” (adjective) or ”the same” (noun) is a good example. 相同 (Pinyin: xiāngtóng) can be read as a pair of tones: a first (high, no variation) and second (ascending). 橡皮 looks at least somewhat similar in Pinyin: xiàngpí. Yet 橡皮 is a not a word closely related to 相同. 橡皮 is Mandarin for “rubber” or, more colloquially, “eraser.” Breaking this word down, we can appreciate that 橡皮 is comprised of a rather different pairing of tones: fourth (descending) and second (ascending).

Tone pairs in practice

Can practicing common tone pairings help you improve the accuracy of your Mandarin pronunciation? Tone pair drills are certainly popular in classrooms, as well as for those looking to take a more do-it-yourself approach to learning Mandarin. A systematic approach to tone pairs typically takes the learner from relatively simple tone combinations to more complex contour progressions. From easiest to most difficult, these tone pairs are:

- First-First

- Fourth-Fourth

- Second-Fourth

- Second-Second

- Fourth-Second

- First-Fourth

- Second-Third

- Third-Third

- First-Third

- Second-First

- Third-Fourth

- Third-First

- First-Second

- Fourth-First

- Fourth-Third

- Third-Second

Luckily, getting familiar with the proper pronunciation of many essential Mandarin expressions is enough to start you on your way towards better recognizing tone pair patterns.

- 医生, yīshēng, “doctor” (First-First)

- 再见, zàijiàn, “goodbye” (Fourth-Fourth)

- 城市, chéngshì “city, town” (Second-Fourth)

- 国籍, guójí, “nationality, country of citizenship” (Second-Second)

- 面条, miàntiáo, “noodles” (Fourth-Second)

- 天气, tiānqì, “the weather” (First-Fourth)

- 没有, méiyǒu, “no” (Second-Third)

- 你好, nǐ hǎo, “hello” (Third-Third)

- 邀请, yāoqǐng, “invite” (First-Third)

- 明天, míngtiān, “tomorrow” (Second-First)

- 马上, mǎshàng, “Immediately, right away” (Third-Fourth)

- 始终, shǐzhōng, “always; from beginning to end” (Third-First)

- 中国, zhōngguó, “China” (First-Second)

- 上班, shàngbān, “to work” (Fourth-First)

- 上午, shàngwǔ, “morning” (Fourth-Third)

- 选择, xuǎnzé, “select, choose” (Third-Second)

Drilling yourself on these words and their constituent tones can also help you dissociate inflection from emotion or mood. Remember: in Mandarin, tonalities must be perceived differently than they are in most Western languages. Paying close attention to the tonal qualities of “beginner’s Mandarin” can help you to habituate yourself not just to how Mandarin is spoken, but how it is heard.

Do you have any experience teaching or learning tone pairs? What other tips and tricks have helped you get in tune with Mandarin pronunciation? Let us know in the comments below.

Want To Learn Chinese? Join uS To Learn More!