Feng shui (风水 fēng shuǐ) means “wind water” in Chinese, and is the art of channeling natural energy called “qi” (气 qì) to benefit our health, energy, and wealth. According to feng shui, the proper arrangement of objects in our living spaces will deflect bad qi, and beckon the good qi to flow in our lives. Setting aside the more superstitious elements of feng shui, most of the basic principles of the practice make a lot of practical sense. For instance, feng shui takes advantage of natural elements in our world like sunlight or greenery so we can be more in tune with our body’s natural inclinations. Scientists have found that color strongly affects our psychology and physiology, something feng shui was on to a long time ago. Feng shui is an ancient art with many superstitious elements, but many of its applications have striking relevance today as they are grounded in the age-old human interaction with nature.

Related: 9 Simple Feng Shui Life Hacks

History of Feng Shui

While in the West we are more familiar with feng shui as a modern design fad, it is an art actually as old as Chinese civilization itself. Ancient texts and archeological evidence show a lot of continuity between the way feng shui was practiced in early Chinese civilization and the way it is practiced today. The goal of feng shui has always been to situate humans well within their environment. The perfect spot for a structure would ensure the building occupants benefited from good qi, a universal force that bound the universe, earth, and humanity together. Feng shui was an expression of the way the ancient Chinese saw their relationship with the universe. Starting around 4,000 years ago, all Chinese capitals began to be built on a north-south axis. As Chinese rulers saw themselves as the intermediaries between heaven and earth, this axis of orientation emphasized the role of the capital city between what was considered to be the cardinal direction of the element of earth at the south gate, and heaven in the north. Inside Chinese palaces, the emperor’s residence would be on the north side and would feature larger buildings, while the southernmost corner would house servants in low-lying quarters, reflecting the Confucian social hierarchy. The alignment of Chinese capitals along earth’s polar axis was also symbolic of unity and harmony with nature. The north-south axis can still be seen in the grid layout of modern day cities like Beijing.

Modern Revival

While suppressed during purges of feudal superstitions in China in the 1970’s, feng shui gained popularity as an interior design fad in the West, after Nixon’s visit to China warmed the Western world to ideas from the East. The advertising world pounced on feng shui, reinventing it for Western consumption, in the meanwhile, drawing many critics who claimed that the original meaning of feng shui had been lost in translation. Robert Todd Carroll, author of “The Skeptic’s Dictionary,” wrote, “alleged masters of feng shui now hire themselves out for hefty sums to tell people such as Donald Trump which way his doors and other things should hang. Feng shui has also become another New Age ‘energy’ scam with arrays of metaphysical products.”

While it seems ironic that Trump would be keen on ancient Chinese principles that emphasize a calm and harmonious environment, he was one of the first proponents of feng shui in the West. In 1995, recognizing influx of Asian investors into the property market, Trump spent $230 million making the Trump Tower adhere to feng shui principles. Trump's feng shui master, a 27-year-old female practitioner from New York Chinatown, initially found the building in a very poor state of feng shui. She demanded to have complete control over the renovations, to which the normally hard-nosed Trump obliged, if only not to miss out on the opportunity not to miss out on the Asian market. The now-famous building featured a golden globe structure to deflect the negative energy from the street, and tea colored window glass to absorb negative energy from the climate and environment.

Backlash against traditional thinking in 20th century China has left the percentage of Chinese people who believe in feng shui today to only about a third. However, feng shui has been making a steady comeback since the economic reforms of Deng Xiaopeng, as China’s growing wealth and increasing interest in its past has supported the return of some traditional trades. Feng shui masters in Hong Kong, where the business of feng shui consultancy persisted through modernization, are often consulted by tycoons from the mainland for advice on how to improve their fortunes with good qi. Foreign companies in China are also making an attempt to acknowledge feng shui. In 2005, Hong Kong Disneyland shifted its main gate twelve degrees to appeal to local cultural tastes. A Shanghai-based practitioner interviewed in a CCTV report on the contemporary practice of feng shui said that many of his clients were foreign companies. Prominent academics like Cao Dafeng, vice-president of Fudan University in Shanghai, are studying feng shui in a bid to bring more national attention to the attributes of ancient art. Meanwhile, less gimmicky feng shui practices in the West still carry weight in their respective areas of design.

Mystical Characteristics of Feng Shui

Feng shui’s architectural principles are cryptically based on the invisible force of qi, which can be directly translated as “air,” but it is more analogous to the universal principles of physics. Qi is the same energy Shaolin monks use to break bricks with their bare hands (here, the movement of qi is a phenomenon proven by medical science), and which Chinese medicine rejuvenates in the body. The concept of qi comes from Daoism, whose central tenet is that energy, or essence, is impermanent in form, and fluid in nature (道可道非常道—The Dao that can be put into words is not the eternal Dao). According to Daoism, water is the ideal state of matter because it flows effortlessly from place to place, knowing instinctively the “way” or the 道 by finding the path of least resistance. While describing architecture in metaphorical terms seems like a lot of superstitious gobbledygook, feng shui can be understood as the attempt to give living spaces a feeling of effortlessness and comfort. For example, in suggesting that a dragon should travel through the chambers of a building before it was constructed, feng shui is suggesting that we look for any awkward turns or cramped spaces in our building designs, the same way that buildings today have to be wheelchair accessible.

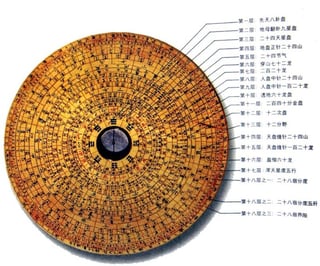

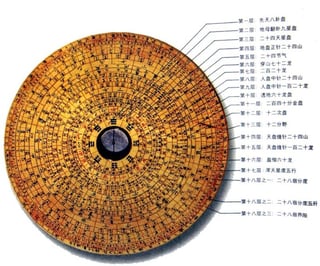

In deciding the exact position of a building and the way it should be constructed, feng shui involved a lot of complex calculations and meticulous attention to detail. The luopan (罗盘 luópán), or magnetic compass, was invented for feng shui purposes and used as a tool for land-based divination before it was ever taken to sea. Luo means everything, and pan means bowl, making the magnetic compass metaphorically a bowl that contains all the mysteries of the universe. One of its functions was to measure various landscape elements, as rivers, hills, or other geographical features were deemed to have some influence on the qi running through the area. Thousands of years before the scientific discovery of magnetic polarity, the ancient Chinese described these forces in terms of yin (feminine receiving force) and yang (masculine pushing force). The balance of these universal forces was essential to finding the right place for a structure with good qi, in the same way that Chinese medicine attempts to restore the balance of yin and yang to the body. Each of eight directions had their own special characteristics of qi, which made it important to choose the right orientation for a structure. In addition, the luopan allowed more precise geographical and climate considerations to be taken into account. Ideal buildings were high and solid towards the north to break the wind, and low and open towards the south to capture light, warmth, and the summer breeze.

Before the invention of the compass, the Form School used geographical features to make feng shui judgments, and was more intuitively based on harmony with natural surroundings. For example, the Form School holds that cities should be built against a mountain range at their north end to block the flow of bad qi. Later, the Compass School developed mechanical techniques to identify the distinct types of qi that come from each of the eight directions, involving complex calculations using instruments such as the luopan.

Image Source

Complex metaphysical calculations also took into account the five elements—metal, earth, fire, water, and wood—which also feature prominently in other disciples stemming from Chinese philosophy like martial arts, medicine, and choosing auspicious names. The five elements, like qi, are invisible forces which destroy and create when interacting with one another. According to Chinese philosophy, earth is a buffer zone in which life can exist because extreme elements and polarities cancel each other out. It is the feng shui architect’s job to balance these five elements against one another, although a great deal of flexibility is allowed when it comes to the design features that elements are incorporated into. The order of architectural application of these elements comes in decreasing order of form, orientation, placement, color, material, texture, and numbers. If there are urban or topographical constraints on the design of the building, then the balance of the elements cannot be achieved in form, for example, then the architect can compensate with colors that would offset the imbalance.

Conclusion

While it might seem strange that a tradition based on metaphysical Daoism that has its hands in architecture, land planning, and interior design, a lot of feng shui principles are seen as quite down-to-earth. Setting aside the more superstitious elements of feng shui, most of the basic principles of the practice make a lot of practical sense. For instance, feng shui takes advantage of natural elements in our world like sunlight or greenery so we can be more in tune with our body’s natural inclinations. Scientists have found that color strongly affects our psychology and physiology, something feng shui was onto a long time ago. As for the more mystical elements of feng shui, whether you are skeptical or not of a placebo effect, sometimes just the belief that something will work is what matters most.

Read Next: 9 Simple Feng Shui Life Hacks

Want To Learn Chinese? Join us to learn more!